BOOK REVIEWS

THE UNREALITY OF MEMORY by Elisa Gabbert (NYT Book Review)

“These days, there’s no dearth of catastrophes to document — and yet, sifting through the data online rarely brings a sense of insight. The more I read, the further I feel from clarity. Writing in oblique reference to the Holocaust and the atrocities of the 20th century, the literary theorist Maurice Blanchot declared that disaster “escapes the very possibility of experience — it is the limit of writing.” Disaster defies not only comprehension but representation: When we try to translate it into language, we grant it a tidy order that contradicts its essential nature.”

NEW PEOPLE by Danzy Senna (NYT Book Review)

“‘The term post-racial is almost never used in earnest,’ wrote Ta-Nehisi Coates in a 2015 post on The Atlantic’s website, describing it instead as a means of discussing our progress toward a utopian moment that may never arrive. It is difficult to look at the word today and imagine the hope and credulity with which it was once invested: These days, people who possess faith in the possibility of the post-racial are usually those who’ve already experienced a measure of its promised ease, as they pass relatively unimpeded through a relatively white world. But in “New People,” her captivating and incisive fifth book, Danzy Senna has crafted a tragicomic novel that powerfully conjures the sense of optimism once associated with future racial transcendence, even as it grounds that idealism in a present that bears more than just a family resemblance to the racialized past.”

MY YEAR OF REST AND RELAXATION by Ottessa Mosfegh (Vanity Fair)

“As one fighting not to enter society but to exit from it, Moshfegh's protagonist is an unlikely revolutionary. In the century-plus since "The Yellow Wallpaper" was published, as women have gained more control over their bodies and property and general happiness, they've actively been encouraged to work: To work at getting ahead, building a career, building a family, building good credit. To work at relationships, professional and personal. To work at 82 cents on the average man's dollar. And then, also, to work toward perfecting their pore size, their abs, their core, their back-of-ann fat. Being a woman has become a full-time job. We tend to think that a deeply ingrained system, such as capitalism, can be resisted only by equal and opposite action—but in a culture based upon striving, might it be more radical for women to opt out? Moshfegh's narrator's final gesture, transforming herself into a piece of half-living art, echoes the odd and combative passivity of Herman Melville's Bartleby, a scrivener who suddenly, inexplicably, refuses to perform his duties. Bartleby stands taciturn in the corner of his law office, offering no explanation for his refusal other than that he'd ‘prefer not to.’”

COMPANIONS by Christina Hesselholdt (NYT Book Review)

“These ruptures are overt signs of more subtle shifts the characters undergo as they live, love and grow older, but Hesselholdt’s most penetrating insights into the texture of lived experience come in moments of vivid imagery and unexpected humor, which bridge the weight of biography and the lightness of an instant. Baby sharks in a pet-store aquarium “are gray and look like ferocious anchors”; a red leaf is “a slice of autumn.” In a breathtaking and inexplicably memorable scene, Alwilda parts ways with a young American she has met at a bar. Suddenly he reappears with his friends, all of them on bikes. ‘Without stopping he reached out a long arm and grabbed my head and kissed me, impressively well coordinated,’ Alwilda recounts. ‘He is far too young. I won’t call him.’”

WHEN WATCHED by Leopoldine Core (NYT Book Review)

““When Watched,” Leopoldine Core’s first collection of short stories, dwells in the realm of the sparkling mundane, the type of human matter that is invitingly recognizable, the type of matter that you yourself have participated in or observed. Written exclusively in the third person and unfolding almost in real time, Core’s stories have a voyeuristic quality, like peering through the windows of a ground-floor apartment as you walk by. In one story, two women are spending time together at the tail end of a long and promising date, when one suddenly tires of the other and asks her to leave. In another, a woman watches a man she is in love with, but does not know very well, choosing fruit in a grocery store. An old couple abandon a cross-country drive and end up taking a bus and a plane the rest of the way. A disappointed writer senses the dissolution of his marriage — perhaps mistakenly.”

PEACES by Helen Oyeyemi (NYT Book Review)

“Halfway through, Oyeyemi achieves the impossible: She unstirs the soup, reconstituting the links that bind her eccentric cast of characters to one another, to the mysterious circumstances of Ava’s isolation, and to an additional, unforeseen character: Premysl Stojaspal, the son of the influential Karel Stojaspal, an artist who paints all-white canvases that reveal themselves differently to each viewer. Prem, whose claim to existence is even more fragile than that of the train, has appeared in some form to each of the train’s passengers — except for Ava, who has never managed (or perhaps never been willing) to catch even a glimpse of him. Though the narrative never strays from a tone that is light, agile and unsentimental, here its emotional stakes are clarified: What are the consequences of going unseen by the one person whom you most wish to perceive you?”

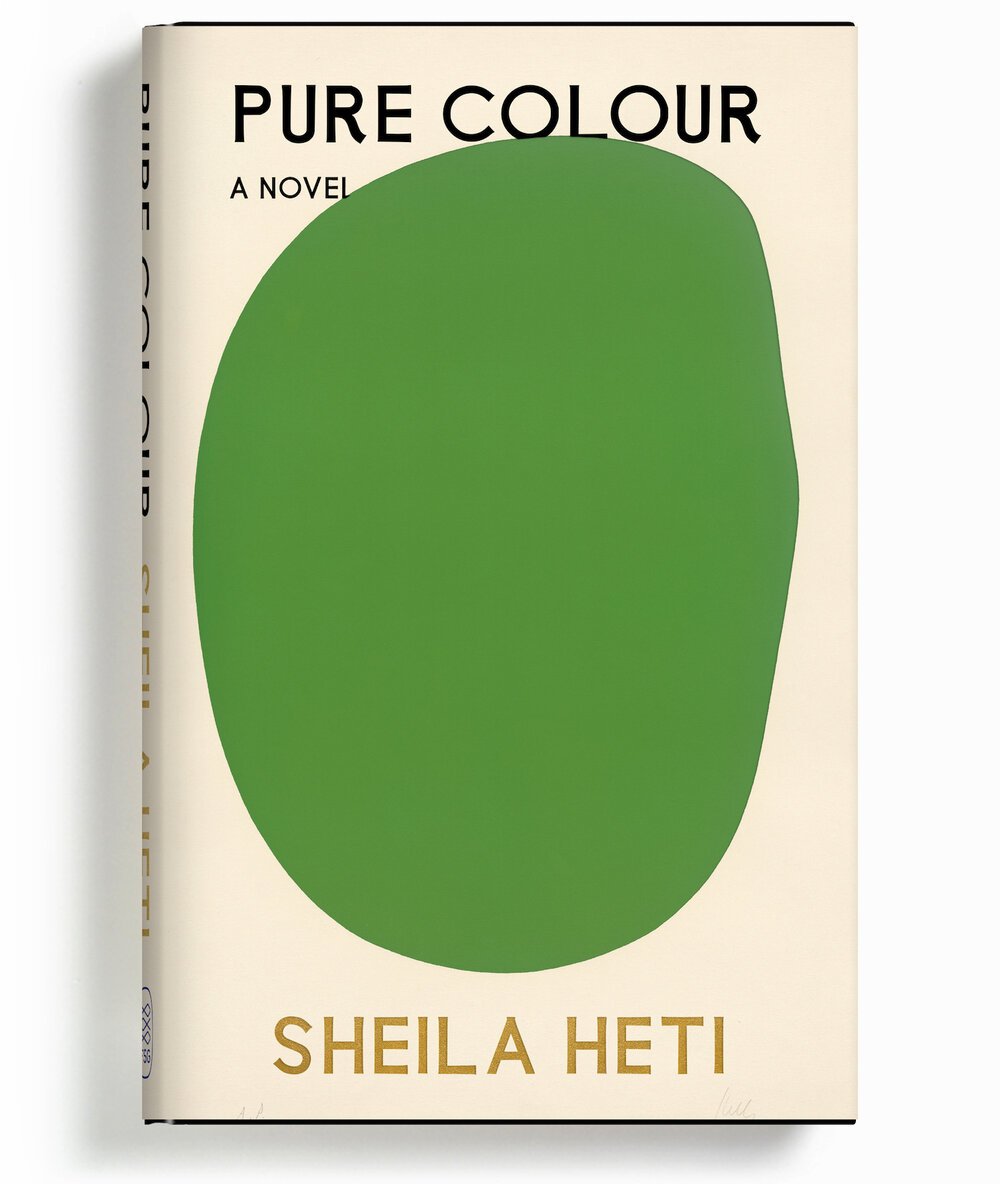

PURE COLOUR by Sheila Heti (NYT Book Review)

“The category of the “big book” in literature can often seem monolithic: a fetish object telegraphing excellence, a genre represented often literally by door-stopper page counts, and by names so famous they hardly need to be mentioned again here. But there are certain books that possess a different strain of vastness, elliptical and elusive, the way the coiled interior of a conch seems to contain the roar of the sea. In these works, you sense the subtle expansiveness of an individual life — the product of internal focus rather than literal sprawl. And who’s to say that one vastness is bigger than another? Who can measure, much less compare, at such incommensurable scales? Though “Pure Colour” is a slim volume, approximately the thickness of a nice slice of sourdough bread, it holds within it a taste of something that defies classification. As Heti writes: “There is something exciting about a first draft — anarchic, scrappy, full of life, flawed. A first draft has something that a second one has not.” That something doesn’t always survive into the final product, but it is the artist’s purest self, unadulterated.”

Where novels are often described as ambitious, and omnivorous, short stories are rarely presumed to have appetites — to run rampant through the reader’s mind, ravenous, devouring, feral. The most common metaphors that try to sum up the particular work a short story can do are postcards and photo albums, icebergs and carefully etched cameos: still, patient objects putting themselves on calm display. Perhaps that’s why the fierce little machines found in the Taiwanese American writer K-Ming Chang’s first collection, “Gods of Want” — the successor to her gutsy debut novel, “Bestiary” — feel so unexpected: Each one is possessed of a powerful hunger, a drive to metabolize the recognizable features of a familiar world and transform them into something wilder, and achingly alive.

GHOST MUSIC by An Yu (NYT Book Review)

“Ghost Music” inverts the tropes of the ghost story, which often feature spirits acting out in the violent, passionate way of the living — hurling objects from tabletops, demanding recognition and restitution — instead drawing the familiar world of human life closer to the enigmatic realm of the dead. Song Yan, Bowen and his mother go through the daily choreographies of their lives and occupations without complaint, haunting well-worn routines in the same way a spirit might haunt a former home.

Unable to fully accept or reject their circumstances, unable to let go of old attachments or hold tightly enough to them to remain grounded, the living characters who populate the novel seem more adrift than the ghosts. In one early encounter, the eerie mushroom-like entity asks Song Yan for help. “It is normal that you don’t understand,” it tells her. “But when you leave this room … I’d like you to remember me.” What comes to feel most mournful about Yu’s human characters is their inability to express their desires, to translate their intense longing into a simple request.